The writer of this article is Brahma Chellaney who is professor of strategic studies at the Centre for Policy Research and the author of the forthcoming book 'Water, Peace, and War: Confronting the Global Water Crisis (Oxford University Press)'.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In an increasingly water-stressed world, shared water resources

are becoming an instrument of power, fostering competition within

and between nations. The struggle for water is escalating

political tensions and exacerbating impacts on ecosystems.

This week’s Budapest World Water Summit is the latest initiative in

the search for ways to mitigate the pressing challenges.

Consider some sobering facts:

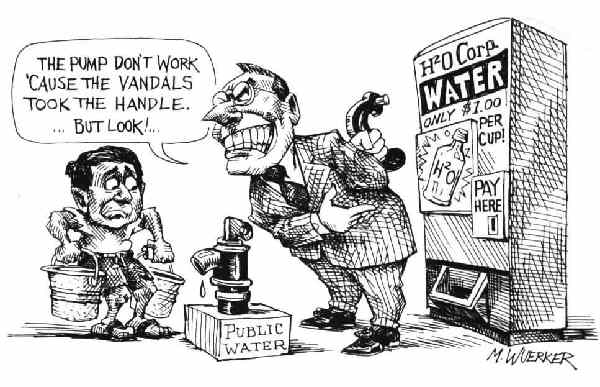

- Bottled water

at the grocery store is already more expensive than crude oil on the

international spot market.

- More people in

the world today own or use a mobile phone than have access to water

sanitation services.

- Unclean water

is the greatest killer on the globe, yet a fifth of humankind still lacks

easy access to potable water.

- More than half

of the global population currently lives under water stress—a figure

projected to increase to two-thirds during the next decade.

Adequate access to natural resources, historically, has been a key

factor in peace and war.

- Water, however, is very

different from other natural resources.

- There are substitutes for a

number of resources, including oil, but none for water.

- Countries can import, even

from distant lands, fossil fuels, mineral ores, and resources originating

in the biosphere.

- But they cannot import the

most vital of all resources, water—certainly not in a major or sustainable

manner. Water is essentially local and thus very expensive to ship across

seas.

Rapid economic and demographic expansion, however, has already

turned potable water into a major issue across large parts of the world.

Lifestyle changes, for example, have spurred increasing per capita water

consumption in the form of industrial and agricultural products.

- Consumption growth has become the single biggest driver of water stress. Rising incomes, for example, have promoted changing diets, especially a greater intake of meat, whose production is notoriously water-intensive.

- It is about 10 times more water-intensive to produce meat than plant-based calories and proteins.

US intelligence has warned that such water conflicts could turn

into real wars. According to a report reflecting the joint judgement of US

intelligence agencies, the use of water as a weapon of war or a tool of

terrorism will be more likely in the next decade in some regions.

Commercial or state decisions in many countries on where to set up

new manufacturing or energy plants are increasingly being constrained by

inadequate local water availability.

The World Bank has estimated the economic cost of China’s water

problems at 2.3% of its gross domestic product. China,

however, is not as yet under water stress—a term internationally defined as the

availability of less than 1,700 cubic metres of water per head per year. The

already water-stressed economies, stretching from South Korea and India to

Egypt and Morocco, are paying a higher price for their water problems.

- In fact, water is becoming

the world’s next major security and economic challenge.

- Although no modern war has

been fought just over water, this resource has been an underlying factor

in several armed conflicts.

- With the era of cheap,

bountiful water having been replaced by increasing supply and quality

constraints, the risks of overt water wars are now increasing.

Averting water wars needs rules-based

cooperation, water sharing and dispute settlement mechanisms. However, there is

still no international water law in force, and most of the regional water

agreements are toothless, lack monitoring and enforcement rules and provisions

to formally divide water among users.

Worse still, unilateralist appropriation

of shared resources is endemic where autocrats rule.

- For example, China rejects

the very concept of water sharing and is working to have its hand on

Asia’s water tap by building an extensive upstream

hydro-infrastructure.

- India, by contrast, has a

water-sharing treaty with each of the two countries located downstream to

it—Pakistan and Bangladesh.

- Indeed, the only Asian

treaties that incorporate a specific sharing formula on cross-border river

flows are those covering the Indus and the Ganges.

- Both these treaties set new

principles in international water law: the 1996 Ganges pact guarantees

Bangladesh an equal share of the downstream flows in the most difficult

dry season, while the earlier 1960 Indus treaty remains the world’s most

generous water-sharing arrangement, under which India agreed to set aside

80.52% of the waters of the six-river Indus system for Pakistan

indefinitely in the naïve belief that it could trade water for peace.

A central issue facing Asia is not the readiness to accommodate

China’s rise but the need to persuade China’s leaders to institutionalize

cooperation with its neighbours on shared resources. China already boasts more

dams than any other country in the world. And its rush to build yet more dams,

especially giant ones, promises to roil relations across Asia. If China

continues on its current course, prospects for a rules-based Asian order could

perish forever.

Moral of the Story

!!

Water poses a more intractable problem for the world than peak

oil, economic slowdown and other oft-cited challenges. Addressing this core

problem indeed holds the key to dealing with other challenges because of

water’s nexus with global warming, energy shortages, stresses on food supply,

population pressures, pollution, environmental degradation, global epidemics

and natural disasters.