अप्रैल 1965 में कच्छ के रन पर हमले के बाद अगस्त में कश्मीर में घुसपैठ प्रारम्भ कर पकिस्तान ने दोनों देशों के मध्य युद्ध की स्थिति उत्पन्न कर दी

WHO won the war then ?

While both India and Pakistan celebrate the golden jubilee of

their glorious “victories”, newspaper columns and TV shows in the two countries

have belatedly tried to adjudicate the winner. From India’s point of view, this

debate is futile. First of all, this debate presupposes that war outcomes are

binary in nature. While some commentators have pointed out that 1965 ended in a

stalemate, a large body of public opinion thinks of war outcomes as a zero sum

game where Pakistan’s loss implies India’s win. This is not necessarily true.

Victory—perceived or otherwise—depends on each side’s political objectives,

which may not always amount to Clausewitzian destruction of the enemy.

What is important for India is not the war outcome but the lessons

we should have learnt from 1965, but sadly we haven’t yet.

First, 1965 was a huge intelligence failure.

- Despite

the foreboding Rann of Kutch skirmish in April 1965, India failed in

anticipating the nefarious Operation Gibraltar being schemed in

Pakistan.

- Fast

forward to Kargil in 1999 or Parliament attacks in 2001 or the 26/11

Mumbai episode in 2008, the implications of persistent intelligence lapses

are too massive to be ignored.

- We

have repeatedly allowed Pakistan to take us by surprise despite knowing

the nature of the Pakistani state rather too well.

Second, Indian forces have had to suffer from poor equipment and

ammunition support whether it was 1965 or the Kargil war.

- During

the former, our 1945 vintage Centurion tanks were up against the latest

American origin M-47 and M-48 Patton tanks.

- Three

and a half decades later, the Kargil Review Committee catalogued the

deficiency of weapons and equipment support for Indian Army jawans.

- A

CAG report tabled in Parliament earlier this year raised questions on

India’s ability to fight a 20-day war.

- The

story is worse with paramilitary and police forces which have to deal with

insurgents and infiltrators too often.

- Poor training and equipment of Punjab police was on full public display during the recent Gurdaspur attacks.

Third, the quality of decision-making during times of crisis leaves

a lot to be desired.

- Since

the debacle of 1962 was blamed on excessive political interference, 1965

was characterized by inadequate civilian oversight which—according to

military historian Srinath Raghavan—was the reason India did not achieve a

better outcome.

- Army

chief general J.N. Chaudhuri miscalculated the amount of ammunition left

and the number of tanks destroyed, an assessment which prodded Prime

Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri to accept the ceasefire under international

pressure.

The lessons from 1965 will remain incomplete till the events in

Tashkent are understood in entirety.

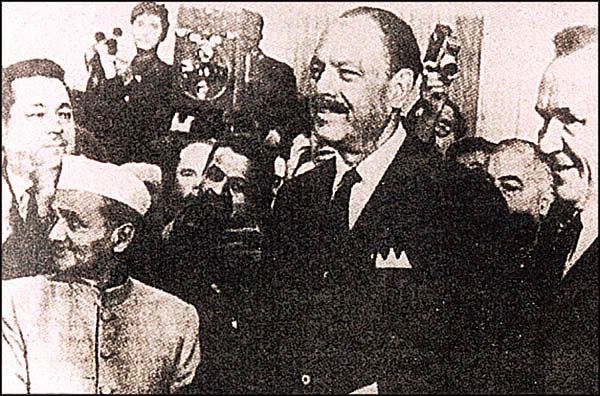

Following the cease-fire after the Indo-Pak War

of 1965, a Russian sponsored agreement was signed between India and Pakistan in

Tashkent on 10 January 1966.

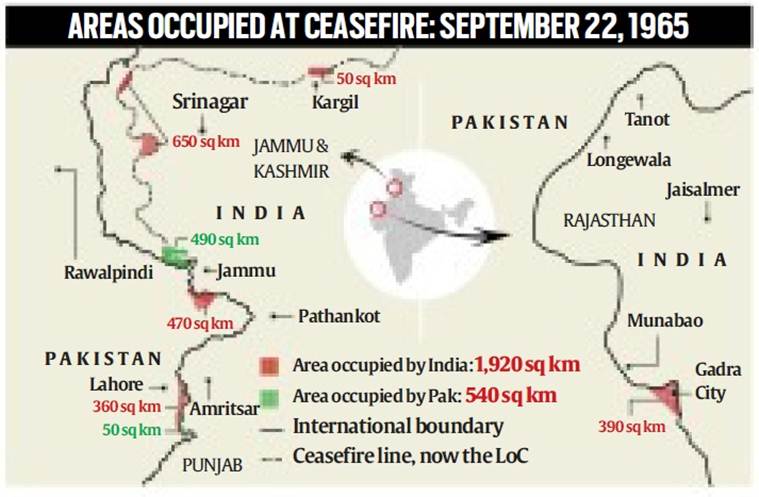

- India

had captured four times the territory Pakistan did during the war.

- Under

Soviet pressure, India ceded all its gains which could have served as

leverage with Pakistan in future negotiations.

- It

seemed as if lessons from the adverse fallout of international mediation

in Kashmir sought by Jawaharlal Nehru were not yet internalized.

- K.

Shankar Bajpai, who served as secretary to the Indian delegation in

Tashkent, recalls, “We went determined not

to return them (the captured areas), unless Pakistan agreed to renounce

force and accept the ceasefire line as a frontier.”

- Apparently,

the threat of referral to UN Security Council without the cover of Soviet

veto did the trick.

Mistake of returning Hajipir !

- Under

the agreement, India agreed to return the strategic Haji Pir pass to

Pakistan which it had captured in August 1965 against heavy odds and at a

huge human cost.

- The

pass connects Poonch and Uri sectors in Jammu and Kashmir and reduces the

distance between the two sectors to 15 km whereas the alternate route

entails a travel of over 200 km.

|

- India

got nothing in return except an undertaking by Pakistan to abjure war, an

undertaking which meant little as Pakistan never had any intention of

honouring it.

- Return of the vital Haji Pir pass was a mistake of

monumental proportions for which India is suffering to date.

- In addition to denying a direct link between Poonch and

Uri sectors, the pass is being effectively used by Pakistan to sponsor

infiltration of terrorists into India.

- Inability to resist Russian pressure was a manifestation

of the boneless Indian foreign policy and shortsighted leadership.

Analyzing Tashkent as per what K

Shanker Bajpai writes in Indian express !!

The Tashkent Declaration turns 50 in

four months. But it fits here, having been forever questioned for returning

heroically captured J&K areas. We went determined not to return them,

unless Pakistan agreed to renounce force and accept the ceasefire line as a

frontier.

We did face unexpected difficulties:

Russia’s skilful diplomacy turned from pro-Indian to

even-handed, seeing possibilities of weaning

Pakistan away from its then bugbear China. Originally urging the Tashkent meet

not for a final settlement but to start a process, Moscow pressed for an

agreement there and then, with messages sent through our ambassador warning of

a return to the UN Security Council, and without the benefit of a Soviet veto.

-

Many states have defied UN resolutions,

but that was not our way. Shastriji had his foreign and defence ministers,

principal secretary, foreign, home and defence secretaries, as well as the

incoming army chief with him. The decision was not one man’s, but of our usual

type. But in all fairness, one must remember that diplomacy can only reflect

the ground situation, not least the totality of state capability. Some of us

dearly preferred other outcomes, but one could do no more at Tashkent than we

could on the ground.

What positives happened due to 1965

experience ?

1. Growth of Indo- Russia

relations - Russia not only vetoed against a resolution against India, but also

provided her with military hardwares and provided for ceasefire negotiations in

Tashkent.

2. The war lifted Indian spirit after defeat against China. It also cut down

Pakistan's nerves who had assumed India to be weak.

3. The war coupled with the twin droughts of 1965-66 highlighted India's

weakness on food security front. US suspended PL-480 food aid. This

incentivised focus towards Green Revolution.

4. The war also accelerated our nuclear programme. Shortly after, we conducted

our first nuclear bomb at Pokhran in 1974.

5. War heralded unity between the various factions. PM Lal Bahadur Shastri led

at the forefront with his slogans like 'Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan '

Moral of the story --

- Pakistan’s

1965 gamble failed, but we only “scotched the snake, not killed it”.

- This

snake cannot be killed, or even defanged now. We have to immunise

ourselves.

- That

means making ourselves so capable as to live with the likely worst, while

warily preparing for worse still.

- Howsoever

right an objective, it is feasibility that counts.

- In

1965, we were economically floundering, militarily weak, politically

bickering, and still diplomatically inexperienced. The lessons of 1965 —

not to be any of those things — are obvious. So too is our refusal to

learn.