The rapid

growth of mobile telephony in India ranks inarguably as one of India’s greatest

success stories. Cheap telephone connectivity has empowered individuals in

myriad ways, and has served as a massive productivity multiplier for the

economy by collapsing communication costs.

It is

important to trace the history of telephony and draw lessons from this success

story, for such successes have been rare in our history

There are two facts about the telecom boom that

are obvious but merit repetition—

- first, the growth was driven by the private sector,

not state-owned companies or the government; and

- second, the boom has been brought about by the rapid

uptake of mobile telephony, not landline telephones or public call office

(PCO) booths.

How NTP - 1999 was a game changer ?

The New Telecom Policy

(NTP) announced by the government of India on 3 March 1999 recounted some facts

about the status of the telecom sector in India at the time. It noted that

India had “over 1 million” mobile phone subscribers. Ten years after Rajiv

Gandhi’s government left office in 1989 and eight years after Pitroda returned

to the US, following Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination, tele-density moved from 0.6%

in 1989 to 2.8% in 1999

Does that

constitute a “revolution” and does that make Rajiv Gandhi and Sam Pitroda the

progenitors of the mobile revolution?

- Recent data says that India had over 700 million active mobile phone connections as of October 2012, catapulting the telecom penetration rate from less than 3% in 1999 to over 70% as of October 2012 and fast closing in on developed world standards.

- The 1999 NTP has far exceeded its own target of

achieving 15% tele-density by 2010, which would have probably sounded

overly optimistic when announced in 1999. How did this massive growth

happen? Does any specific individual or policy deserve more credit than

others?

Speaking at a corporate

awards function in December 2009 where his company was felicitated, Idea

Cellular’s then managing director Sanjeev Aga was asked to identify what in his

view marked the turning point for India’s telecom sector. Aga pointed to the

1999 NTP, saying: “When I read it today, it is still contemporary and

comprehensive.” Aga characterized the NTP as a “watershed event”

In his book, India—The Emerging Giant, Columbia

University’s Professor Arvind Panagariya also addresses the question of what

catalysed growth in telecom.

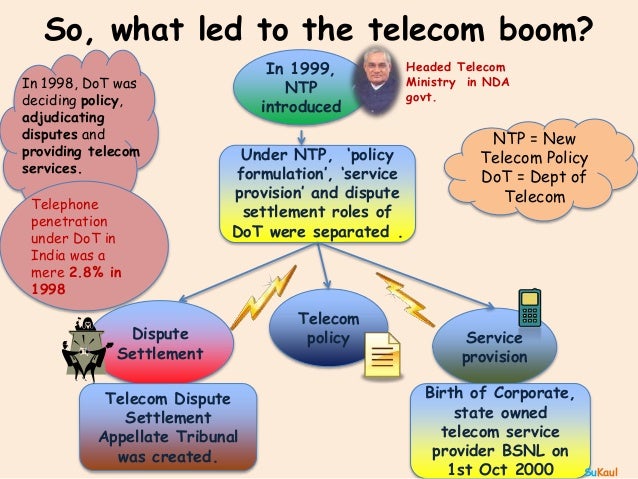

- Panagariya writes that key policy reforms were implemented by the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government in 1999, with one of the most important measures being separation between policy formulation and service provision, culminating with the birth of Bharat Sanchar Nigam Ltd (BSNL) on 1 October 2000.

- Getting rid of this very obvious conflict of interest

freed the telecom sector from political control. Vajpayee, who also held

the telecom portfolio at the time, took the politically difficult step of

corporatizing BSNL, and Panagariya writes that the prime minister

personally intervened to push through this deep structural reform.

The creation of BSNL

- The creation of BSNL wasn’t easy—Panagariya writes that 400,000

department of telecommunications (DoT) employees went on a long strike to

oppose it. Though the Vajpayee government conceded almost all their

demands, there was no going back on the fundamental principle of

separating policy formulation from service provision and the accompanying

corporatization

- Besides this step, the 1999 NTP separated the DoT’s regulatory and dispute settlement roles too, with the creation of the Telecom Dispute Settlement Appellate Tribunal.

- Before these reforms, the DoT was deciding policy for

the sector, adjudicating disputes and providing telecom services. That

such glaring conflicts of interest persisted for so many decades reflects

on the calibre and intent of the governments that preceded the Vajpayee

administration.

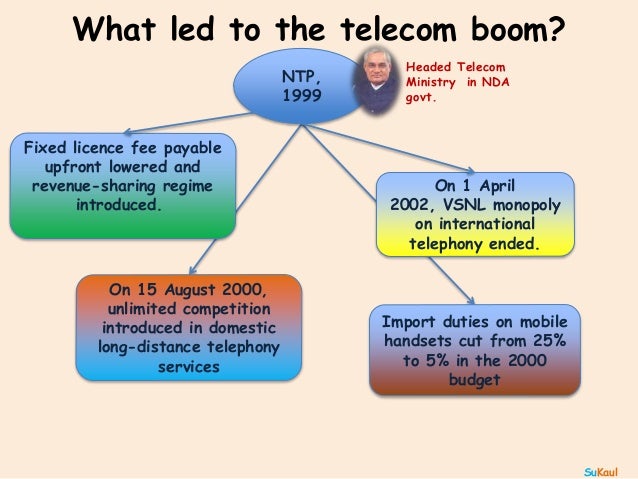

- Under the 1999 NTP, the fixed licence fee payable upfront

was lowered with the government introducing a revenue-sharing regime.

The media was very hostile

to the new policy. Frontline magazine ran a stinging critique of the policy,

holding former prime minister Vajpayee guilty of “a new standard of

impropriety”. Outlook magazine said that Vajpayee’s moves “had all the

trappings of a financial scam”

- On 15 August 2000, “unlimited competition” was

introduced in domestic long-distance telephony services.

- Just as importantly, import duties on mobile handsets

were cut from 25% to 5% in the 2000 budget delivered by Yashwant

Sinha.

- On 1 April 2002, Videsh Sanchar Nigam Ltd’s monopoly

on international telephony ended.

Panagariya documents all

these changes painstakingly in his book, and it is these changes that deserve

credit for the rapid increase in tele-density over the last decade

- Pitroda, in fact, torpedoed attempts to bring mobile telephony to India in 1987, as Panagariya records.

- DoT had received World Bank funding to deploy a

cellular network in Bombay (as the city was then called), with Sweden’s

Ericsson winning the project.

- Panagariya writes that Pitroda, who was heading the

Centre for Development of Telematics (CDoT), created at his behest by

Indira Gandhi in August 1984, went to the media arguing that “luxury car

phones” were “obscene” in a nation where “people were starving”.

Pitroda’s intervention

escalated the issue to Rajiv Gandhi, who pulled the plug on what would have

probably been India’s first cellular network deployment. Panagariya cites this

case as an example of how turf wars within government arise in response to

policy changes: because Pitroda felt that mobile telephony threatened his work

at CDoT, he did not hesitate to use his influence to stop what may have been a

better way to achieve the outcome of increasing tele-density

As the data bears out, Pitroda’s strategy to

grow tele-density through indigenous development in CDoT failed conclusively.

Pitroda did not return to India till 2004, when the Congress party formed the

Union government once again.

The results speak for themselves: Rajiv Gandhi and

Pitroda’s model of promoting indigenous technology with the DoT trying to meet

demand for telephones did not succeed, whereas the Vajpayee government’s

policies curtailed the state’s role and created space for private entrepreneurs

to deliver cheap and reliable telecom service speedily on a massive scale.

The former tried to grow by state-led indigenization, the latter threw open the sector to competition and entrepreneurship.

India’s telecom story is a

shining testament to how policy clarity, political conviction for reforms and

private entrepreneurship can deliver outcomes, within a decade, that government

intervention and well-intentioned bureaucratic thinking cannot even conceive

of. The lesson from India’s telecom boom is that curtailing government control

and public-sector clout in sectors such as agriculture, mining, defence, power,

ports and banking can deliver similar outcomes—and no amount of spin doctoring

by any individual or political party should be allowed to detract from this

lesson.